(Giveaway info will be at the very end of this post.)

I’d like to discuss some aspects of magic in fantasy novels, specifically how the magic in my novel Rast both differs from and coincides with that used as a plot device in other novels.

First, in my novel, magic is described as a power active in a particular place; the magic kingdom of Rast, ruled by a Drogar, the sorcerer king. But later developments reveal that there is also another realm where magic is mastered, Easderly, where cousins of the sorcerer king reside, and from where a daughter has to be sent to be mother of a future sorcerer king. This is similar to the treatment in other works as well as folklore, where special places exist where magic happens – in Fairie or Lord Dunsany's The King of Elfland's Daughter. In fact, the latter work has a fairy princess necessary to bear a future magic king – clearly testimony to the power of magic’s distant influences, because I’d never heard of that novel before researching for this blog post.

In this discussion I will assume (drearily lacking any sense of wonder) that in both the reader and

The World in the Satin Bag has moved to my new website. If you want to see what I'm up to, head on over there!

Showing posts with label Fantasy Factoids. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Fantasy Factoids. Show all posts

Thursday, April 21, 2011

Friday, April 23, 2010

International SF/F: Does it get an out from the "cliche" argument?

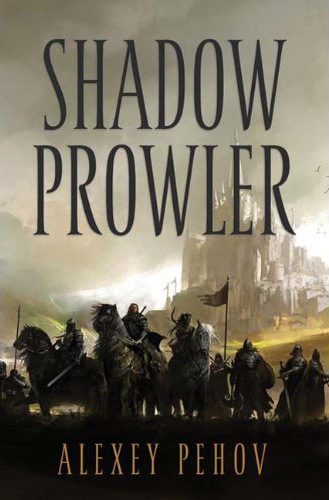

I've been meaning to talk about this subject for a while, and it is result of an experience I had a few weeks ago when the fine folks over at Tor sent me Alexey Pehov's Shadow Prowler.

I am, by all accounts, somewhat more critical of fantasy for its lack of originality than I am of other genres. It's not an unusual position to take, since so many arguments launched against various fantasy titles typically include terms like "derivative" or "Tolkien-esque" and so on. The genre is saturated with familiar tropes. But, as I've argued many times before, a good writer can take a fairly cliche idea and make it good. Additionally, Sometimes the way a book presents itself (i.e. via the cover and the cover synopsis) can alleviate a lot of the knee-jerk reactions readers may have when they discover a new fantasy title. It is this reaction that I want to talk about here.

When I received Shadow Prowler in the mail, I was immediately pleased by the cover (see above), which led me straight to the text on the cover jacket. That is where the problems started. The description of Pehov's story is, to put it mildly, about as cliche as it gets. Read for yourself:

When I received Shadow Prowler in the mail, I was immediately pleased by the cover (see above), which led me straight to the text on the cover jacket. That is where the problems started. The description of Pehov's story is, to put it mildly, about as cliche as it gets. Read for yourself:

To end this, I have a few questions:

--Does international SF/F get an out from the "cliche" argument simply because it is international? (apply this to any international SF/F, not just Russian)

--Is it a good thing that one can go from being annoyed to being excited about a book due entirely to the discovery of its international origins?

I feel uneasy saying yes to the first question, simply because of the stages many developing or developed nations go through in terms of genre fiction (you can, largely speaking, trace the same general literary developments in science fiction in just about every nation, with some exceptions). And, I feel uneasy saying no to the last question, because excitement for any text is a good thing; if my interest in this text leads me to read it and, perhaps, love it, it might engender a willingness to open my mind to more fiction in this particular vein and more fiction from international venues (which I'm already fairly open to, though I don't go out of my way to find the stuff, with exception to Caribbean SF--more on that some other time).

What do you think? Am I insane? Has this ever happened to you?

I am, by all accounts, somewhat more critical of fantasy for its lack of originality than I am of other genres. It's not an unusual position to take, since so many arguments launched against various fantasy titles typically include terms like "derivative" or "Tolkien-esque" and so on. The genre is saturated with familiar tropes. But, as I've argued many times before, a good writer can take a fairly cliche idea and make it good. Additionally, Sometimes the way a book presents itself (i.e. via the cover and the cover synopsis) can alleviate a lot of the knee-jerk reactions readers may have when they discover a new fantasy title. It is this reaction that I want to talk about here.

When I received Shadow Prowler in the mail, I was immediately pleased by the cover (see above), which led me straight to the text on the cover jacket. That is where the problems started. The description of Pehov's story is, to put it mildly, about as cliche as it gets. Read for yourself:

When I received Shadow Prowler in the mail, I was immediately pleased by the cover (see above), which led me straight to the text on the cover jacket. That is where the problems started. The description of Pehov's story is, to put it mildly, about as cliche as it gets. Read for yourself:After centuries of calm, the Nameless One is stirring.Great. Another novel about some Nameless One with elfin princesses and a city so cleverly called Avendoom (ha ha ha, get it, Avendoom...and the city is threatened by the Nameless One). But then I read this and my reaction changed:

An army is gathering; thousands of giants, ogres, and other creatures are joining forces from all across the Desolate Lands, united, for the first time in history, under one, black banner. By the spring, or perhaps sooner, the Nameless One and his forces will be at the walls of the great city of Avendoom.

Unless Shadow Harold, master thief, can find some way to stop them.

Epic fantasy at its best, Shadow Prowler is the first in a trilogy that follows Shadow Harold on his quest for a magic Horn that will restore peace to the Kingdom of Siala. Harold will be accompanied on his quest by an Elfin princess, Miralissa, her elfin escort, and ten Wild Hearts, the most experienced and dangerous fighters in their world…and by the king’s court jester (who may be more than he seems…or less).

Reminiscent of Moorcock's Elric series, Shadow Prowler is the first work to be published in English by the bestselling Russian fantasy author Alexey Pehov. The book was translated by Andrew Bromfield, best known for his work on the highly successful Night Watch series.Something about the explanation of the texts' origins caused me to pause. A Russian fantasy epic originally published in Russian? A link to another fantastic series by another Russian SF/F great? Suddenly I was interesting and a little inner dialogue shot off in my head:

Me: Oh, well, he's a Russian author writing fantasy. That's interesting.While the dialogue didn't proceed exactly as described above, it does provide a basis for the complete turnaround I had when I discovered the novel's origins: translated from Russian. I even gawked at my own idiocy. Why was I suddenly okay with a novel that sounds horribly cliched? Why did the fact that it is an international book change my mind? Stranger yet is the fact that I am/was fully aware of the long tradition of genre fiction in Russian history, dating back centuries. But, there I was, suddenly excited about a novel that only moments before I was about to toss onto my "likely will never read because it's too cliche" pile. Maybe it's a good thing, though. Maybe more reactions like this should happen so that novels like Shadow Prowler don't get lost in the sea of English-based fantasy titles loaded with just as many cliches. Something about that makes me feel strange, though.

My Head: So?

Me: So, I want to read it.

My Head: But a minute ago you rolled your eyes and sighed because it sounded too cliche.

Me: Yeah, but that was before I knew he was Russian.

My Head: So, if you're Russian, you can get away with it?

Me: Apparently.

My Head: You realize how stupid that sounds, right?

Me: Quiet, you. You're just my head talking.

To end this, I have a few questions:

--Does international SF/F get an out from the "cliche" argument simply because it is international? (apply this to any international SF/F, not just Russian)

--Is it a good thing that one can go from being annoyed to being excited about a book due entirely to the discovery of its international origins?

I feel uneasy saying yes to the first question, simply because of the stages many developing or developed nations go through in terms of genre fiction (you can, largely speaking, trace the same general literary developments in science fiction in just about every nation, with some exceptions). And, I feel uneasy saying no to the last question, because excitement for any text is a good thing; if my interest in this text leads me to read it and, perhaps, love it, it might engender a willingness to open my mind to more fiction in this particular vein and more fiction from international venues (which I'm already fairly open to, though I don't go out of my way to find the stuff, with exception to Caribbean SF--more on that some other time).

What do you think? Am I insane? Has this ever happened to you?

Monday, April 19, 2010

Science Fiction and Fantasy in Airports

As promised, I do have something interesting to point out about the presence of science fiction and fantasy in airports, and something that might be a good indicator of the power of books among travelers.

First things first, I can honestly say that I've seen a significant increase in the number of book-specific shops in airports. I don't know if this is national or international, but I've traveled a little bit over the last few years and I have noticed two things: 1) that there are more book-specific shops springing up all over the place, and 2) that some areas are insanely more book-friendly than others (St. Louis and Atlanta, for example, have a lot of book shops and places that carry books).

But what is more interesting than this is how strong of a presence science fiction and fantasy have. When you walk into a book-specific shop, there is almost always a section specific to science fiction and fantasy (and a section for YA, which is usually loaded to the teeth with fantasy titles). Sometimes the section is quite small, and other times it's about the same size as all of the other sections (non-fiction, general fiction, and so on).

The only downside to this is that these shops have a tendency to carry very little in terms of new work, which means that many of these SF/F sections are more like the classic literature section that most of these places have. It's unfortunate, but there must be a reason for it; you don't carry old SF/F (as in classic SF/F) if you're not selling it. This isn't to say that these stores don't carry newer titles; they do, but they typically only carry the more prominent new titles, such as works from various high-profile urban fantasy authors or big names in SF literature. But, what's to complain about? They have SF/F in the bookstores in airports!

Now that I've pointed out the more obvious aspects of SF/F's presence in airports, I think it's worth noting the much more hidden and telling presence: book sections within non-book-specific shops.

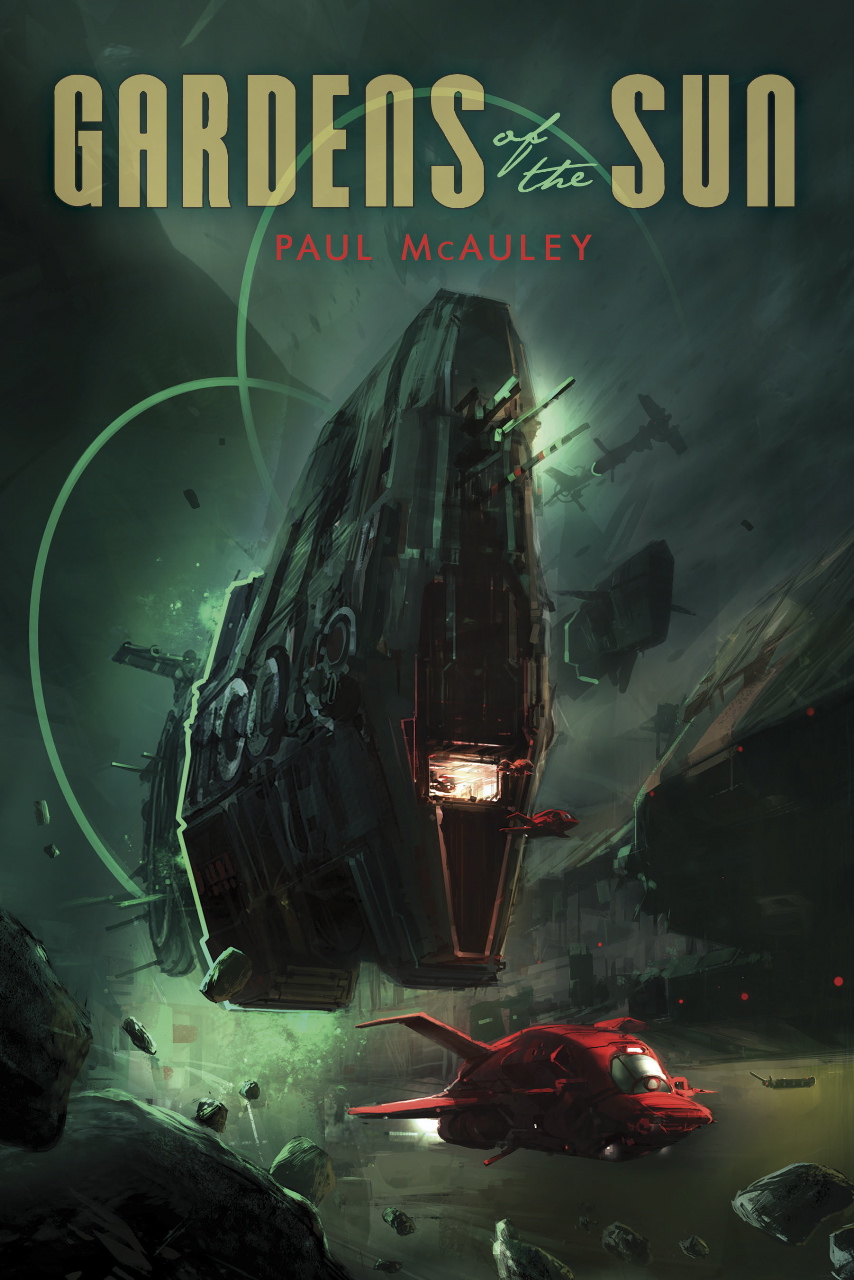

While I was in St. Louis a few weeks back, I decided to check out this little tech shop (headphones, phones, DVDs, games, things like that--InMotion Entertainment, I think) in the airport and was surprised to discover that they had a book section that was not only SF/F friendly, but possibly one of the best SF/F book sections I have seen for the size (four shelves no more than three feet wide). What was so special about it? The titles they carried represented a wide range of unique titles you might not find in your local bookstore, and all of the books had gorgeous covers. They had, for example, Paul McAuley's Gardens of the Sun:

They had loads of other titles too, many of which I hadn't heard of until then and most of which looked fascinating (yes, I've heard of McAuley's work, but I didn't write down the titles of all the others, and I've since forgotten them). I might have bought a book or two if I hadn't already spent over $100 on books during the PCA/ACA conference. The selection was simply fantastic. If you wanted something new and a little less popcorn-y, then you'd have to go to this shop.

They had loads of other titles too, many of which I hadn't heard of until then and most of which looked fascinating (yes, I've heard of McAuley's work, but I didn't write down the titles of all the others, and I've since forgotten them). I might have bought a book or two if I hadn't already spent over $100 on books during the PCA/ACA conference. The selection was simply fantastic. If you wanted something new and a little less popcorn-y, then you'd have to go to this shop.

The point of all of this is that airports are incredibly SF/F friendly. While the selection is not always the greatest (depending on the airport), there are almost always SF/F titles somewhere. I'm not sure what this says about our culture. These stores don't carry SF/F if it doesn't sell, so people must be requesting and buying the stuff. Do SF/F books make great travel reads in the same way that others genres have been for decades? Perhaps.

What do you think?

First things first, I can honestly say that I've seen a significant increase in the number of book-specific shops in airports. I don't know if this is national or international, but I've traveled a little bit over the last few years and I have noticed two things: 1) that there are more book-specific shops springing up all over the place, and 2) that some areas are insanely more book-friendly than others (St. Louis and Atlanta, for example, have a lot of book shops and places that carry books).

But what is more interesting than this is how strong of a presence science fiction and fantasy have. When you walk into a book-specific shop, there is almost always a section specific to science fiction and fantasy (and a section for YA, which is usually loaded to the teeth with fantasy titles). Sometimes the section is quite small, and other times it's about the same size as all of the other sections (non-fiction, general fiction, and so on).

The only downside to this is that these shops have a tendency to carry very little in terms of new work, which means that many of these SF/F sections are more like the classic literature section that most of these places have. It's unfortunate, but there must be a reason for it; you don't carry old SF/F (as in classic SF/F) if you're not selling it. This isn't to say that these stores don't carry newer titles; they do, but they typically only carry the more prominent new titles, such as works from various high-profile urban fantasy authors or big names in SF literature. But, what's to complain about? They have SF/F in the bookstores in airports!

Now that I've pointed out the more obvious aspects of SF/F's presence in airports, I think it's worth noting the much more hidden and telling presence: book sections within non-book-specific shops.

While I was in St. Louis a few weeks back, I decided to check out this little tech shop (headphones, phones, DVDs, games, things like that--InMotion Entertainment, I think) in the airport and was surprised to discover that they had a book section that was not only SF/F friendly, but possibly one of the best SF/F book sections I have seen for the size (four shelves no more than three feet wide). What was so special about it? The titles they carried represented a wide range of unique titles you might not find in your local bookstore, and all of the books had gorgeous covers. They had, for example, Paul McAuley's Gardens of the Sun:

They had loads of other titles too, many of which I hadn't heard of until then and most of which looked fascinating (yes, I've heard of McAuley's work, but I didn't write down the titles of all the others, and I've since forgotten them). I might have bought a book or two if I hadn't already spent over $100 on books during the PCA/ACA conference. The selection was simply fantastic. If you wanted something new and a little less popcorn-y, then you'd have to go to this shop.

They had loads of other titles too, many of which I hadn't heard of until then and most of which looked fascinating (yes, I've heard of McAuley's work, but I didn't write down the titles of all the others, and I've since forgotten them). I might have bought a book or two if I hadn't already spent over $100 on books during the PCA/ACA conference. The selection was simply fantastic. If you wanted something new and a little less popcorn-y, then you'd have to go to this shop.The point of all of this is that airports are incredibly SF/F friendly. While the selection is not always the greatest (depending on the airport), there are almost always SF/F titles somewhere. I'm not sure what this says about our culture. These stores don't carry SF/F if it doesn't sell, so people must be requesting and buying the stuff. Do SF/F books make great travel reads in the same way that others genres have been for decades? Perhaps.

What do you think?

Posted by

Unknown

at

3:00 PM

0

comments

Labels:

Fantasy Factoids,

Literature Rants,

Science Factoids

Labels:

Fantasy Factoids,

Literature Rants,

Science Factoids

Sunday, March 07, 2010

Question: If you were going to teach a class on fantasy literature, what would you cover?

That's a big question. I've always wanted to design an introductory course on science fiction or fantasy (doing both at the same time would be impossible). Selecting texts, however, is always a problem for any genre-specific course. Where do you start? Where do you end? Which movements do you represent or ignore? Do you risk bringing in texts that few people have heard of in the hope of trying to show the true breadth of the fantasy genre, or do you keep it simple and recognizable, at risk of being a little dull or cliche?

Now, I'm no expert on designing literature courses, primarily because I'm a fairly new educator. That said, if I were to devise an introductory sixteen week college course on fantasy literature, it would look something like the following:

Novels, etc. (in order by movement or period)

The Epic of Gilgamesh (pretty much the earliest fantasy text in existence) -- Between 20th and 16th Centuries B.C.E.

The Odyssey by Homer (if any text has been integral to the creation of the modern fantasy genre, it is this one) -- 8th Century B.C.E.

Phantastes by George MacDonald (1858) OR Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll (1865)(either of these texts would be a great introduction to the trend of secondary-world fantasy we are so familiar with today)

The Metamorphosis and Other Stories by Franz Kafka (a lot of classic must-reads for early weird and magical realist writing here) -- 1916-19

The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien (because you have to have it, even if you don't want to) -- 1954-55

Duncton Wood by William Horwood (by far one of the best animal fantasies ever written, but without all the swords and things) -- 1980

The Shadow of the Torturer by Gene Wolfe (a unique and powerful fantasy story worth reading and discussing) -- 1986

Ship of Magic by Robin Hobb (a great book for discussing social dynamics and issues of gender) -- 1999

The House of the Stag by Kage Baker (an excellent modern fantasy tale with a wonderful fairytale twist) -- 2008

Note: I would argue that The Epic of Gilgamesh, Beowulf, and The Odyssey are interchangeable. It really doesn't matter where you start, because you can talk about all three of these texts without putting all of them on the curriculum. It really depends on personal tastes. Personally, I think the ones I selected for the list are more accessible for a more general audience; Beowulf can be a very difficult text for some folks.

I would also recommend shoving The Rings of the Nibelung by Richard Wagner immediately prior to The Lord of the Rings if there is space and time for it; it represents one of the most obvious precursors to Tolkien's greatest works. You could even show the last act of the opera if you're so inclined.

Critical Texts:

The Fantastic by Tzvetan Todorov (offers a provocative theoretical approach to literature and the fantastic) -- 1973

Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion by Rosemary Jackson (another interesting theoretical text that would do some good for engaging with the novels above) -- 1981

Rhetorics of Fantasy by Farah Mendlesohn (possibly one of the best critical texts to be written in the last ten years) -- 2008

Note: Likely the texts in this section would be read in excerpts as supplements to the fiction reading. There are also essays I'd put in here that aren't directly related to fantasy as supplements to specific themes and texts.

I don't know if I'd show movies in such a course. There are a lot of films worth considering. For example, instead of reading The Lord of the Rings, you could having movie nights to watch the films (which I think are better than the books anyway). There are a lot of other interesting films to consider, such as: The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, Legend, or The Fountain.

Looking above, it's clear that I'm leaving out a lot of movements and genres--New Weird, Young Adult Fantasy, Urban Fantasy, and others. It's inevitable, though.

So, any thoughts?

Now, I'm no expert on designing literature courses, primarily because I'm a fairly new educator. That said, if I were to devise an introductory sixteen week college course on fantasy literature, it would look something like the following:

Novels, etc. (in order by movement or period)

The Epic of Gilgamesh (pretty much the earliest fantasy text in existence) -- Between 20th and 16th Centuries B.C.E.

The Odyssey by Homer (if any text has been integral to the creation of the modern fantasy genre, it is this one) -- 8th Century B.C.E.

Phantastes by George MacDonald (1858) OR Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll (1865)(either of these texts would be a great introduction to the trend of secondary-world fantasy we are so familiar with today)

The Metamorphosis and Other Stories by Franz Kafka (a lot of classic must-reads for early weird and magical realist writing here) -- 1916-19

The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien (because you have to have it, even if you don't want to) -- 1954-55

Duncton Wood by William Horwood (by far one of the best animal fantasies ever written, but without all the swords and things) -- 1980

The Shadow of the Torturer by Gene Wolfe (a unique and powerful fantasy story worth reading and discussing) -- 1986

Ship of Magic by Robin Hobb (a great book for discussing social dynamics and issues of gender) -- 1999

The House of the Stag by Kage Baker (an excellent modern fantasy tale with a wonderful fairytale twist) -- 2008

Note: I would argue that The Epic of Gilgamesh, Beowulf, and The Odyssey are interchangeable. It really doesn't matter where you start, because you can talk about all three of these texts without putting all of them on the curriculum. It really depends on personal tastes. Personally, I think the ones I selected for the list are more accessible for a more general audience; Beowulf can be a very difficult text for some folks.

I would also recommend shoving The Rings of the Nibelung by Richard Wagner immediately prior to The Lord of the Rings if there is space and time for it; it represents one of the most obvious precursors to Tolkien's greatest works. You could even show the last act of the opera if you're so inclined.

Critical Texts:

The Fantastic by Tzvetan Todorov (offers a provocative theoretical approach to literature and the fantastic) -- 1973

Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion by Rosemary Jackson (another interesting theoretical text that would do some good for engaging with the novels above) -- 1981

Rhetorics of Fantasy by Farah Mendlesohn (possibly one of the best critical texts to be written in the last ten years) -- 2008

Note: Likely the texts in this section would be read in excerpts as supplements to the fiction reading. There are also essays I'd put in here that aren't directly related to fantasy as supplements to specific themes and texts.

I don't know if I'd show movies in such a course. There are a lot of films worth considering. For example, instead of reading The Lord of the Rings, you could having movie nights to watch the films (which I think are better than the books anyway). There are a lot of other interesting films to consider, such as: The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, Legend, or The Fountain.

Looking above, it's clear that I'm leaving out a lot of movements and genres--New Weird, Young Adult Fantasy, Urban Fantasy, and others. It's inevitable, though.

So, any thoughts?

Posted by

Unknown

at

9:45 PM

2

comments

Labels:

About My Writing,

Fantasy Factoids,

Literature Rants

Labels:

About My Writing,

Fantasy Factoids,

Literature Rants

Tuesday, January 05, 2010

RoF's Women-Only Issue: Good or Bad?

Realms of Fantasy Magazine recently announced that in August of 2011 they will be releasing a special themed issue of the magazine called "Women in Fantasy." The idea is that every department will be dedicated to that theme in some way, and only women can submit.

I have mixed feelings about this:

(Mike Brotherton offers his opinion here.)

I have mixed feelings about this:

- Are they going to do a "Men in Fantasy" issue? If not, why? While I understand the impetus behind creating the issue, it also has the potential to do more harm than good if the RoF folks aren't careful. Yes, there should be more women writers in SF/F, but this is going one step farther by intentionally discriminating based on sex, without considering fairness; it could be seen as playing the payback game rather than doing anything for the community as a whole. This, to me, could be as divisive as all the other discussions begun and ended over the last year.

- I don't think this is nearly as "revolutionary" as the title and the explanation seems to indicate. While there are not enough recognizable female figures in the speculative genres, this is far less true of fantasy than science fiction. Most of the problems with under-representation seem focused more on SF than F. If Analog or Asimov's were doing a similar thing, then not only would there be more of an uproar (for various reasons, many of them wrong), but such as issue would have a greater impact on the genre. Right now? I don't see this as being all that revolutionary when you consider that their primary genre (fantasy) is much more friendly to women than other genres (and no, I am not saying that F is perfect at all).

- I agree with one of the commentators that the "Women in Fantasy" idea comes off very much like a stunt. I don't mind stunts, generally speaking, but when dealing with a clearly sensitive issue, this is problematic.

- I fail to understand why this issue of RoF is "women only" when the theme is "Women in Fantasy." Is there an assumption that men can't properly address the topic? Are men assumed to be less adequate at writing female characters or talking about women figures in fantasy? I don't know. Maybe that's not what they are thinking, but these are things that pop into my head.

- Generally speaking, I like the idea behind it. I think an issue dedicated to the discussion of women in fantasy (including fiction about women in fantasy worlds) is a fantastic idea. It could turn into something stunning, if done right.

(Mike Brotherton offers his opinion here.)

Wednesday, November 18, 2009

Cultural Literacy and Genre Fiction

I've been researching this concept called "cultural literacy" in preparation for my final paper in my pedagogy course. In doing so, I've come to an interesting "revelation," if you will. Science fiction and fantasy are part of our culture as much as something like math or English; they are unconscious elements present in all of us that sometimes make themselves known, and other times remain in the background, operating as little signals in the reaction center of the brain.

The obvious, though, is how science fiction and, to a lesser extent, fantasy have consumed popular culture. As much as all the other elements that seem to make up the culturally literate figure (history by locale, basic science, math, etc., and all those things that make up our language, our thought processes, and our acknowledgment of the social, however minute or forgotten), pop culture as embodied by SF/F has consumed society itself.

Even if you don't want SF/F television or movies, you know about them. Even if you don't read Harry Potter or Twilight, you know about them, and you may even know about all of these things in some basic detail. You know, for example, without having read Twilight, that Meyers wrote a book about vampires and something resembling romance; you know that Harry Potter is about a boy wizard and wizard-like things; you know that Star Wars has the Force and lightsabers and Darth Vader; you know that Star Trek is about humans and some guy with pointy ears traveling around in the universe seeing nifty stuffs. We all know these things (well, almost all of us) in the U.S. (and Canada and the U.K., mostly likely), because they make up a part of who we are and how we communicate with the greater social apparatus.

John Scalzi said it clearly: SF (and you have assume even F, to a lesser extent) has mainstream acceptance. Whether or not it has any other form of acceptance seems irrelevant at this point. SF/F is a part of our culture, part of that cultural literacy that some older theorists have suggested allows every one of us to be able to communicate without confusing the hell out of one another.

And you have to think about that for a minute and bask in the amazing sensation of that feeling. Science fiction and fantasy have become so integral to the social landscape of the U.S. and other countries, that even Shakespeare is being challenged by the new social paradigm.

Having thought all of this, I have only one thing left to say: now what?

The obvious, though, is how science fiction and, to a lesser extent, fantasy have consumed popular culture. As much as all the other elements that seem to make up the culturally literate figure (history by locale, basic science, math, etc., and all those things that make up our language, our thought processes, and our acknowledgment of the social, however minute or forgotten), pop culture as embodied by SF/F has consumed society itself.

Even if you don't want SF/F television or movies, you know about them. Even if you don't read Harry Potter or Twilight, you know about them, and you may even know about all of these things in some basic detail. You know, for example, without having read Twilight, that Meyers wrote a book about vampires and something resembling romance; you know that Harry Potter is about a boy wizard and wizard-like things; you know that Star Wars has the Force and lightsabers and Darth Vader; you know that Star Trek is about humans and some guy with pointy ears traveling around in the universe seeing nifty stuffs. We all know these things (well, almost all of us) in the U.S. (and Canada and the U.K., mostly likely), because they make up a part of who we are and how we communicate with the greater social apparatus.

John Scalzi said it clearly: SF (and you have assume even F, to a lesser extent) has mainstream acceptance. Whether or not it has any other form of acceptance seems irrelevant at this point. SF/F is a part of our culture, part of that cultural literacy that some older theorists have suggested allows every one of us to be able to communicate without confusing the hell out of one another.

And you have to think about that for a minute and bask in the amazing sensation of that feeling. Science fiction and fantasy have become so integral to the social landscape of the U.S. and other countries, that even Shakespeare is being challenged by the new social paradigm.

Having thought all of this, I have only one thing left to say: now what?

Posted by

Unknown

at

7:20 PM

6

comments

Labels:

Fantasy Factoids,

Literature Rants,

Science Factoids

Labels:

Fantasy Factoids,

Literature Rants,

Science Factoids

Monday, November 02, 2009

The Fantastic is in the Genes

If you trace back through time you can see through every generation and era the presence of the fantastic. By fantastic, I mean anything that could be construed as fitting into science fiction, fantasy, magical realism, fairy tale, myth, religion, and any other such genres or subgenres in which something we know is not entirely true occurs. The fantastic is somewhat like a virus in that it worms its way into everything and evolves to fit into new shapes so that it may survive in some sort of dominant mode. So, when I say fantastic, I am using a liberal definition of the term, much as literary theorists have, in some respects.

The fact that the fantastic has survived through generations and eras, despite a monumental effort to suppress certain forms of it, is astonishing, and leads me to conclude that there must be something in us, something wired into our DNA, that makes mankind susceptible to the whims of the fantastic (we'll call it fanty from now on, just so it can have a cute name like SF does--i.e. sciffy--and if you're really clever you'll catch the Firefly/Serenity reference).

The fact that the fantastic has survived through generations and eras, despite a monumental effort to suppress certain forms of it, is astonishing, and leads me to conclude that there must be something in us, something wired into our DNA, that makes mankind susceptible to the whims of the fantastic (we'll call it fanty from now on, just so it can have a cute name like SF does--i.e. sciffy--and if you're really clever you'll catch the Firefly/Serenity reference).

We know this from history: the fantastic is woven into us more finely than a nano-fiber coat (if such a thing exists). The cavemen and other early cultures had some idea what it was, and drew it and exchanged stories about it without realizing that was what they were doing. Numerous religions were founded on the very prospect of the fantastic too, and one cannot deny the relation all religious share to one another, even those religions in existence today. So much of our existence is founded in principles of fantastic discourse as figured through all mediums (fine art, writing, spoken word, etc.).

We know this from history: the fantastic is woven into us more finely than a nano-fiber coat (if such a thing exists). The cavemen and other early cultures had some idea what it was, and drew it and exchanged stories about it without realizing that was what they were doing. Numerous religions were founded on the very prospect of the fantastic too, and one cannot deny the relation all religious share to one another, even those religions in existence today. So much of our existence is founded in principles of fantastic discourse as figured through all mediums (fine art, writing, spoken word, etc.).  So, is it any wonder that fantasy, as a genre, is doing so well, or that science fiction film (and even fantasy film, for the most part) have such a strong hold on the visual market? The fact that young adults and children gobble this stuff up like so much candy is testament to our human desire for the fantastic; as adults, we may shed some of the "silly" aspects of our youth, but there is always that thread (of course, some of us never grow up, and that thread is still wrapped around us as a coat).

So, is it any wonder that fantasy, as a genre, is doing so well, or that science fiction film (and even fantasy film, for the most part) have such a strong hold on the visual market? The fact that young adults and children gobble this stuff up like so much candy is testament to our human desire for the fantastic; as adults, we may shed some of the "silly" aspects of our youth, but there is always that thread (of course, some of us never grow up, and that thread is still wrapped around us as a coat).

Now, the question is: is it possible to cut ourselves off from the fantastic (assuming we wanted to), and if we did, what would the consequences of that be? Would we lose a part of our souls, or would it be like losing a toe (no big deal at all)?

The fact that the fantastic has survived through generations and eras, despite a monumental effort to suppress certain forms of it, is astonishing, and leads me to conclude that there must be something in us, something wired into our DNA, that makes mankind susceptible to the whims of the fantastic (we'll call it fanty from now on, just so it can have a cute name like SF does--i.e. sciffy--and if you're really clever you'll catch the Firefly/Serenity reference).

The fact that the fantastic has survived through generations and eras, despite a monumental effort to suppress certain forms of it, is astonishing, and leads me to conclude that there must be something in us, something wired into our DNA, that makes mankind susceptible to the whims of the fantastic (we'll call it fanty from now on, just so it can have a cute name like SF does--i.e. sciffy--and if you're really clever you'll catch the Firefly/Serenity reference). We know this from history: the fantastic is woven into us more finely than a nano-fiber coat (if such a thing exists). The cavemen and other early cultures had some idea what it was, and drew it and exchanged stories about it without realizing that was what they were doing. Numerous religions were founded on the very prospect of the fantastic too, and one cannot deny the relation all religious share to one another, even those religions in existence today. So much of our existence is founded in principles of fantastic discourse as figured through all mediums (fine art, writing, spoken word, etc.).

We know this from history: the fantastic is woven into us more finely than a nano-fiber coat (if such a thing exists). The cavemen and other early cultures had some idea what it was, and drew it and exchanged stories about it without realizing that was what they were doing. Numerous religions were founded on the very prospect of the fantastic too, and one cannot deny the relation all religious share to one another, even those religions in existence today. So much of our existence is founded in principles of fantastic discourse as figured through all mediums (fine art, writing, spoken word, etc.).  So, is it any wonder that fantasy, as a genre, is doing so well, or that science fiction film (and even fantasy film, for the most part) have such a strong hold on the visual market? The fact that young adults and children gobble this stuff up like so much candy is testament to our human desire for the fantastic; as adults, we may shed some of the "silly" aspects of our youth, but there is always that thread (of course, some of us never grow up, and that thread is still wrapped around us as a coat).

So, is it any wonder that fantasy, as a genre, is doing so well, or that science fiction film (and even fantasy film, for the most part) have such a strong hold on the visual market? The fact that young adults and children gobble this stuff up like so much candy is testament to our human desire for the fantastic; as adults, we may shed some of the "silly" aspects of our youth, but there is always that thread (of course, some of us never grow up, and that thread is still wrapped around us as a coat).Now, the question is: is it possible to cut ourselves off from the fantastic (assuming we wanted to), and if we did, what would the consequences of that be? Would we lose a part of our souls, or would it be like losing a toe (no big deal at all)?

Monday, October 19, 2009

Science Fiction's Not Dead, Fantasy is in the Golden Age

People are talking about the death of science fiction again. It's not actually dead, far from it, but as soon as someone says "it's dead" someone else goes crazy (either because they believe SF has long been dead or because they're tired of hearing the argument). Apparently the genre has a few dozen lives and manages to die and be resurrected ten or so times a year. The End of the Universe said science fiction has nine lives, but I think that's too conservative of an estimate. It's died at least that many times in this year alone...

The problem with science fiction isn't that it's dead. To be fair to the genre, it's never actually died, but it has been overshadowed to varying degrees in history. Even in its supposed "Golden Age" science fiction was not exactly as popular people seem to remember. Yes, it was popular, but science fiction never had the popularity of mainstream pop-fiction. That's not to say it was irrelevant or that no science fiction books sold well enough to make it to the bestseller's list; quite a few actually did, but in comparison to traditionally larger genres (romance and quasi-mysteries), it really didn't make the crossover into market dominance at any point in its multi-century lifespan.

Fantasy, on the other hand, has, and not because the genre is necessarily better (and neither is it worse). Fantasy is doing well because it got lucky. Now, to be fair to fantasy, it has always done rather well ever since Tolkien became a persistent model for other fantasy writers. As a genre, fantasy had a lot of uphill battles to fight to get to a point where it had a secure market, but once it got there it never let it go. Now, however, fantasy has exploded. Some have said that fantasy is experiencing a "Golden Age" of its own--and I would have to agree. Why?

Well, as unpredictable as the market often is in regards to what will be the hot item of the year, I would say that fantasy simply got lucky. The publishers had no way of knowing that urban fantasy would plow through the roof like it did, or that other forms of fantasy (more traditional forms, if you will, and even the exceedingly non-traditional--literary, ultra-weird, etc.) would grow moderately over the last couple decades. It just happened.

Now, if I were to argue for a reason, I would say that the last eight years have had a lot to do with the rise of fantasy. Publisher Weekly almost acknowledged as much in the last year when the recession hit and sales of escapist titles (science fiction and fantasy) actually rose (it was temporary in the sense that, while people were going to SF/F for a presumed escape from the present, the downturn of the economy eventually led to an almost universal drop in sales in almost all markets, some of which have yet to fully recover). The reality seems to be that when the proverbial crap hits the fan, readers flock to literature that is less likely to make matters worse. They want heroes and adventures, of a sort. I don't know if this is true for everyone, but sales seem to reflect that. I am unsure how urban fantasy fits into this assessment--UF tends to be somewhat dark in nature. Either we have to accept that people are somewhat darker at heart than we ever anticipated, or urban fantasy offers a bit of harmless, well, fantasy.

I don't know how long fantasy's "Golden Age" will last. As with all booms in literature, there are limits, and I suspect that urban fantasy, which seems to be the genre largely pulling fantasy up out of the pool, will eventually wear out its welcome--fantasy, as a whole, will not. For now, we can sleep soundly knowing that science fiction isn't dead and fantasy is doing quite well. That's good news.

The problem with science fiction isn't that it's dead. To be fair to the genre, it's never actually died, but it has been overshadowed to varying degrees in history. Even in its supposed "Golden Age" science fiction was not exactly as popular people seem to remember. Yes, it was popular, but science fiction never had the popularity of mainstream pop-fiction. That's not to say it was irrelevant or that no science fiction books sold well enough to make it to the bestseller's list; quite a few actually did, but in comparison to traditionally larger genres (romance and quasi-mysteries), it really didn't make the crossover into market dominance at any point in its multi-century lifespan.

Fantasy, on the other hand, has, and not because the genre is necessarily better (and neither is it worse). Fantasy is doing well because it got lucky. Now, to be fair to fantasy, it has always done rather well ever since Tolkien became a persistent model for other fantasy writers. As a genre, fantasy had a lot of uphill battles to fight to get to a point where it had a secure market, but once it got there it never let it go. Now, however, fantasy has exploded. Some have said that fantasy is experiencing a "Golden Age" of its own--and I would have to agree. Why?

Well, as unpredictable as the market often is in regards to what will be the hot item of the year, I would say that fantasy simply got lucky. The publishers had no way of knowing that urban fantasy would plow through the roof like it did, or that other forms of fantasy (more traditional forms, if you will, and even the exceedingly non-traditional--literary, ultra-weird, etc.) would grow moderately over the last couple decades. It just happened.

Now, if I were to argue for a reason, I would say that the last eight years have had a lot to do with the rise of fantasy. Publisher Weekly almost acknowledged as much in the last year when the recession hit and sales of escapist titles (science fiction and fantasy) actually rose (it was temporary in the sense that, while people were going to SF/F for a presumed escape from the present, the downturn of the economy eventually led to an almost universal drop in sales in almost all markets, some of which have yet to fully recover). The reality seems to be that when the proverbial crap hits the fan, readers flock to literature that is less likely to make matters worse. They want heroes and adventures, of a sort. I don't know if this is true for everyone, but sales seem to reflect that. I am unsure how urban fantasy fits into this assessment--UF tends to be somewhat dark in nature. Either we have to accept that people are somewhat darker at heart than we ever anticipated, or urban fantasy offers a bit of harmless, well, fantasy.

I don't know how long fantasy's "Golden Age" will last. As with all booms in literature, there are limits, and I suspect that urban fantasy, which seems to be the genre largely pulling fantasy up out of the pool, will eventually wear out its welcome--fantasy, as a whole, will not. For now, we can sleep soundly knowing that science fiction isn't dead and fantasy is doing quite well. That's good news.

Posted by

Unknown

at

6:47 PM

3

comments

Labels:

Fantasy Factoids,

Literature Rants,

Science Factoids

Labels:

Fantasy Factoids,

Literature Rants,

Science Factoids

Thursday, October 08, 2009

Capitalist Fantasy: Where’s it at?

I had an interesting though the other day. With the exception of urban fantasy, which tends to take place in an nearby past or version of the present (with varying degrees of separation), the fantasy genre lacks a capitalist vein. Science fiction, of course, has plenty of this, but why doesn’t fantasy?

The obvious answer is: time period. Most fantasy is written in a pseudo-medieval period with significant resemblance to medieval Europe with exceptional variations (the inclusion of magic, fantastic creatures, and different locales). Since capitalism did not exist in such periods, it makes sense that such places would not be run by capitalist structures. To be fair, medieval Europe was not capitalist primarily because of two factors (at least as I understand it): slow transportation and medieval feudalism. It’s difficult to imagine an economic system like capitalism functioning in a place that is not only seemingly run by an authoritarian figure whose personal rules stand for the word of God (more or less), but also incapable of supporting a system that needs to change, adapt, and move at a rapid pace. Fantasy, thus, enacts this real-world lack; capitalism does not exist there because, as in our world, it cannot.

But why not? With magic such a prevalent force in many fantasies, why wouldn’t we see more of the capitalist structures that made up early capitalist America (or Britain, for that matter)? Magic lends itself so well to being a commodity, for good or bad. You can look to some of the strongest examples of late in which a market is given shape, and yet nothing in that shape indicates any sort of logical economic type. Harry Potter, for example, has Diagon Alley, and Gringott’s Bank, but yet we hear nothing of wages. We’re told there are rich and poor families, but it seems that the richest families embody the nobility and the poorest seem, more or less, like peasants. All of this is on purpose, I suppose, because capitalism is not a central theme, or even a side theme; capitalism is not important to Harry Potter. But why shouldn’t it be? Why does fantasy have to ignore these significant social issues in exchange for the adventures and prophecies (not all fantasy does this, but the stereotype of the genre is not unfounded).

I suppose what I’m asking is: where are my capitalist fantasies? Double entendres are clever!

The obvious answer is: time period. Most fantasy is written in a pseudo-medieval period with significant resemblance to medieval Europe with exceptional variations (the inclusion of magic, fantastic creatures, and different locales). Since capitalism did not exist in such periods, it makes sense that such places would not be run by capitalist structures. To be fair, medieval Europe was not capitalist primarily because of two factors (at least as I understand it): slow transportation and medieval feudalism. It’s difficult to imagine an economic system like capitalism functioning in a place that is not only seemingly run by an authoritarian figure whose personal rules stand for the word of God (more or less), but also incapable of supporting a system that needs to change, adapt, and move at a rapid pace. Fantasy, thus, enacts this real-world lack; capitalism does not exist there because, as in our world, it cannot.

But why not? With magic such a prevalent force in many fantasies, why wouldn’t we see more of the capitalist structures that made up early capitalist America (or Britain, for that matter)? Magic lends itself so well to being a commodity, for good or bad. You can look to some of the strongest examples of late in which a market is given shape, and yet nothing in that shape indicates any sort of logical economic type. Harry Potter, for example, has Diagon Alley, and Gringott’s Bank, but yet we hear nothing of wages. We’re told there are rich and poor families, but it seems that the richest families embody the nobility and the poorest seem, more or less, like peasants. All of this is on purpose, I suppose, because capitalism is not a central theme, or even a side theme; capitalism is not important to Harry Potter. But why shouldn’t it be? Why does fantasy have to ignore these significant social issues in exchange for the adventures and prophecies (not all fantasy does this, but the stereotype of the genre is not unfounded).

I suppose what I’m asking is: where are my capitalist fantasies? Double entendres are clever!

Saturday, September 19, 2009

Talk Like a Pirate Day: Fast Ships, Black Sails!

Avast! Today be Talk Like a Pirate Day, a day o' rejoicin' an' rum drinkin' for all pirates everywhere. On such a day we be needin' to set sail on the high seas to spread the word o' somethin' tha pulls us all together with it's piratey goodness! Cap'in's Ann and Jeff Vandermeer's anthology Fast Ships, Black Sails, published by the fine sailors at Night Shade Books and smuggled to all th' corners o' the earth by Amazon. The tome, fer those wi' the cunning t'read it, is packed like a barrel o'salt pork ready fer a month at sea wi' tales o' our fine people set in fantastical an' science fictional places.

Fast Ships, Black Sails is penned by a fine collection o' landlubberly scribes like Kage Baker, an' Elizabeth Bear. Fine tellers o' tales they be, some o' the best!

Inside this tome ye can find:

"Raising Anchor" - Ann & Jeff VanderMeer

"Boojum" - Elizabeth Bear and Sarah Monette

"Araminta, or, The Wreck of the Amphidrake" - Naomi Novik

"Avast, Abaft!" - Howard Waldrop

"I Begyn as I Mean to Go On" - Kage Baker

"Castor on Troubled Waters" - Rhys Hughes

"Elegy for Gabrielle, Patron Saint of Healers, Whores and Righteous Thieves" - Kelly Barnhill

"Skillet and Saber" - Justin Howe

"The Nymph's Child" - Carrie Vaughn

"68˚06'N, 31˚40'W" - Conrad Williams

"Pirate Solutions" - Katherine Sparrow

"We Sleep on a Thousand Waves" - Brendan Connell

"Pirates of the Suara Sea" - David Freer & Eric Flint

"Voyage of the Iguana" - Steve Aylett

"Iron Face" - Michael Moorcock

"A Cold Day in Hell" - Paul Batteiger

"Captain Blackheart Wentworth" - Rachel Swirsky

"The Whale Below" - Jayme Lynn Blaschke

"Beyond the Sea Gate of the Scholar-Pirates of Sarskoe" - Garth Nix

Fine tales, to be sure, from fine scribes, new an' old. If yer in a piratey mood, pillage yeself some dubloons and buy it. Night Shade Books has some mighty fine tales fer sale, an' they're a small press, so buyin' their tomes helps them keep their ship afloat!

So, matey, find yeself a bookseller and hand over those dubloons, or ye might find yerself walkin' the plank! Arr!

(Thank to Capt'n Bourneville fer translatin' me landlubber speak into th' true tongue!)

Fast Ships, Black Sails is penned by a fine collection o' landlubberly scribes like Kage Baker, an' Elizabeth Bear. Fine tellers o' tales they be, some o' the best!

Inside this tome ye can find:

"Raising Anchor" - Ann & Jeff VanderMeer

"Boojum" - Elizabeth Bear and Sarah Monette

"Araminta, or, The Wreck of the Amphidrake" - Naomi Novik

"Avast, Abaft!" - Howard Waldrop

"I Begyn as I Mean to Go On" - Kage Baker

"Castor on Troubled Waters" - Rhys Hughes

"Elegy for Gabrielle, Patron Saint of Healers, Whores and Righteous Thieves" - Kelly Barnhill

"Skillet and Saber" - Justin Howe

"The Nymph's Child" - Carrie Vaughn

"68˚06'N, 31˚40'W" - Conrad Williams

"Pirate Solutions" - Katherine Sparrow

"We Sleep on a Thousand Waves" - Brendan Connell

"Pirates of the Suara Sea" - David Freer & Eric Flint

"Voyage of the Iguana" - Steve Aylett

"Iron Face" - Michael Moorcock

"A Cold Day in Hell" - Paul Batteiger

"Captain Blackheart Wentworth" - Rachel Swirsky

"The Whale Below" - Jayme Lynn Blaschke

"Beyond the Sea Gate of the Scholar-Pirates of Sarskoe" - Garth Nix

Fine tales, to be sure, from fine scribes, new an' old. If yer in a piratey mood, pillage yeself some dubloons and buy it. Night Shade Books has some mighty fine tales fer sale, an' they're a small press, so buyin' their tomes helps them keep their ship afloat!

So, matey, find yeself a bookseller and hand over those dubloons, or ye might find yerself walkin' the plank! Arr!

(Thank to Capt'n Bourneville fer translatin' me landlubber speak into th' true tongue!)

Posted by

Unknown

at

2:31 PM

6

comments

Labels:

Announcements,

Fantasy Factoids,

Promo Bits,

Science Factoids

Labels:

Announcements,

Fantasy Factoids,

Promo Bits,

Science Factoids

Monday, September 07, 2009

World Building: Thoughts and Practices

World building is one of those things you have to do, even if you don't want to. Whether you write fantasy, science fiction, or something else entirely, you'll always find yourself attempting to build your world, whether at the micro or macro levels. Creating characters is a form of world building, and if all you do is create unique characters for your novels, then you are as much a part of the process as someone who builds entire worlds (they just have to spend more time creating things from scratch, while you, perhaps, can sit around in the comfort of the world you know).

I've often approached world building from a relatively minimalist position. While I enjoy fantasy worlds with richly developed worlds, sometimes such things can get in the way and what should be a riveting novel can turn into a foray into the author's world building practices. Nobody wants that. Tolkien, for all his brilliance in creating the most fully-realized fantasy world in the history of the genre, was occupied by unfortunate flaws in style and character development, some of which were a product of the times. I prefer to keep things localized. Whether it is the most efficient method, I don't know, but it seems to work well enough for me. I don't occupy myself with excessive amounts of ancient history, because, as much as that might be interesting, it is not relevant to whatever story I am writing at that moment.

When I build worlds, I start with names and general ideas, work my way to a map, and then go wild until I feel that I know enough about the world to be able to write in it. Sometimes it works well, depending on how interested I am in a particular world, and sometimes it doesn't. But when it works, it really works. I have three fantasy worlds that I developed this way (Traea, the world in which The World in the Satin Bag is set, a world where I've set many of my "quirky" fantasy stories, and the Mundoscurad, the most recent, in which The Watchtower is set.

There are an absurd amount of different methods for world building, from genre specific to author specific. Writers of all genres, particularly newer writers, are always looking for the "best way," not realizing that the "best way" is really non-existent. Reality dictates that what might work for some, may not work for you, and vice versa. Ken McConnell, for example, said via his Twitter that, "sometimes it's the little things, like word choice that can set the tone and enrich your world building."

So what do you do when it comes to world building? How do you find the right method for you?

Trial and error. Not the answer you were looking for, were you? Tough. So much of writing involves trying something to see if it works for you. If it doesn't, you drop it and try something else. Trial and error is a writer's third or fourth, or maybe tenth, best friend (no doubt writers have a lot of best friends).

But that's neither here nor there. I want to hear about your world building methods. How do you approach creating new worlds? What works for you?

I've often approached world building from a relatively minimalist position. While I enjoy fantasy worlds with richly developed worlds, sometimes such things can get in the way and what should be a riveting novel can turn into a foray into the author's world building practices. Nobody wants that. Tolkien, for all his brilliance in creating the most fully-realized fantasy world in the history of the genre, was occupied by unfortunate flaws in style and character development, some of which were a product of the times. I prefer to keep things localized. Whether it is the most efficient method, I don't know, but it seems to work well enough for me. I don't occupy myself with excessive amounts of ancient history, because, as much as that might be interesting, it is not relevant to whatever story I am writing at that moment.

When I build worlds, I start with names and general ideas, work my way to a map, and then go wild until I feel that I know enough about the world to be able to write in it. Sometimes it works well, depending on how interested I am in a particular world, and sometimes it doesn't. But when it works, it really works. I have three fantasy worlds that I developed this way (Traea, the world in which The World in the Satin Bag is set, a world where I've set many of my "quirky" fantasy stories, and the Mundoscurad, the most recent, in which The Watchtower is set.

There are an absurd amount of different methods for world building, from genre specific to author specific. Writers of all genres, particularly newer writers, are always looking for the "best way," not realizing that the "best way" is really non-existent. Reality dictates that what might work for some, may not work for you, and vice versa. Ken McConnell, for example, said via his Twitter that, "sometimes it's the little things, like word choice that can set the tone and enrich your world building."

So what do you do when it comes to world building? How do you find the right method for you?

Trial and error. Not the answer you were looking for, were you? Tough. So much of writing involves trying something to see if it works for you. If it doesn't, you drop it and try something else. Trial and error is a writer's third or fourth, or maybe tenth, best friend (no doubt writers have a lot of best friends).

But that's neither here nor there. I want to hear about your world building methods. How do you approach creating new worlds? What works for you?

Posted by

Unknown

at

5:20 PM

9

comments

Labels:

About My Writing,

Fantasy Factoids,

Writing Elements

Labels:

About My Writing,

Fantasy Factoids,

Writing Elements

Saturday, September 05, 2009

Fantasy Essentials: What Should I Have Read?

Somewhere along the line I began getting criticized for not being all that great at writing fantasy because I had not read enough in the genre. Maybe this is true, and if so, I would like to rectify that, to the best of my ability.

So, to all those reading this, I’m calling on you for help. In the comments, let me know which five fantasy novels you think I absolutely must read. They can be any fantasy novel except the following: The Lord of the Rings, Eragon, Harry Potter, and George R. R. Martin. I’ve either already read those or tried to read them, so including them here would be meaningless at the moment.

Have at it. Tell me which five you think I should read and why!

So, to all those reading this, I’m calling on you for help. In the comments, let me know which five fantasy novels you think I absolutely must read. They can be any fantasy novel except the following: The Lord of the Rings, Eragon, Harry Potter, and George R. R. Martin. I’ve either already read those or tried to read them, so including them here would be meaningless at the moment.

Have at it. Tell me which five you think I should read and why!

Wednesday, September 02, 2009

Punking Everything in SF/F (Part Two): The Past (Punk)

Wouldn't it be amazing if the strange words and concepts we have so gloriously accepted into pop culture were actually understood as the culturally/socially complex entities that they actually are by the same people that pass around the suffix "punk" like a beer keg at a frat party? Indeed, it would, but the curious thing about modern (or perhaps postmodern) culture is that much of the youth, the very ones who so readily claim to exist within the subcultural group called "punk," who rage against the machine of authority without realizing that their vocal and visual forms of resistance (and even auditory through the likes of Green Day and their ilk) are nothing more than a continuation of consumer culture at its worst/best, have no idea, and no intention of learning, what the word "punk" actually means, or what its placement in human history entails for their strangely lucrative subculture. If that seems like a mouthful, it is, because the very nature of consumer culture is itself a conundrum of modern and postmodern ideals, clashing and wandering through a wasteland of personally useless nonsense, filled with people who are either dolefully aware of the pointless nature of their consumption of things or unwittingly a part of it. This is not to say that consumer culture, or, perhaps we should use its proper name, capitalism (late or otherwise), is necessarily bad. Rather, this paragraph begins to illustrate the reality of our existence in America and other Western capitalist democracies (or fascist states, where such things exist) and how pervasive capitalism is in our lives, so much so that many of us fail to notice its pull and tug on our pocket books. Teenagers today, for all their eccentricities and attempts at genuine resistance, have simply adopted a lifestyle or perception of the world that has been just as commodified as any other movement, ideal, and substance we have thus far conceived.

Where am I getting at with this? The very nature of "punk," as I conceive it, is that it cannot ever truly reject the dominant culture, capitalism, not if it, as a movement, expects to survive. Here you might ask: what is "punk?" You would be right to ask that.

Punk originated, somewhat, in music in the 1970s or so, as many have claimed. True punk, the real, commodity-rejecting monstrosity that emerged quite literally as a counter-culture rather than a subculture, was largely a response to globalization, urbanity, and post-industrialization, an inherently commodity-rich point in our history that readily acknowledged the corporation as almost human. Curious as that may sound, it seems to make sense, because as capitalism began to spread across the globe, largely not by its own steam, but through the hands of those with the guns, so to speak, it gave new powers to the corporate entity to represent itself as a thing that could "speak for itself." More curiosity abounds here as to why it took hardly any time at all for something inhuman in nature, almost robotic, to assume the vocalized subaltern without having had to shed blood in the process; well, at least not the corporate blood, but certainly the blood of pre-nationalist societies consumed into globalizing nationhood.

Punk originated, somewhat, in music in the 1970s or so, as many have claimed. True punk, the real, commodity-rejecting monstrosity that emerged quite literally as a counter-culture rather than a subculture, was largely a response to globalization, urbanity, and post-industrialization, an inherently commodity-rich point in our history that readily acknowledged the corporation as almost human. Curious as that may sound, it seems to make sense, because as capitalism began to spread across the globe, largely not by its own steam, but through the hands of those with the guns, so to speak, it gave new powers to the corporate entity to represent itself as a thing that could "speak for itself." More curiosity abounds here as to why it took hardly any time at all for something inhuman in nature, almost robotic, to assume the vocalized subaltern without having had to shed blood in the process; well, at least not the corporate blood, but certainly the blood of pre-nationalist societies consumed into globalizing nationhood.

Punk, to try to simplify here for brevity, invented for us the teenager as a market niche. Now, once relegated to the status of children, the budding adult had a place of his or her own, a place of music, bad or good, you pick, and protest against the "man." How silly, then, that punk itself vied to create its own subculture as a consumer aggregate, with no real interest in affecting change at all. In its non-conformist nature, punk literally created a subculture that would eventually have its own marketplace, its own capitalist structures a la Hot Topic and other such gothic-ally obsessed teen hideouts. And teenagers bought into it, hook, line, and sinker, not necessarily through some malicious attempt on the part of punk itself, but because punk provided a place for them to go, where their voices could be heard by someone, even if that someone could do nothing to alleviate the perceived issues of society itself.

Punk, to try to simplify here for brevity, invented for us the teenager as a market niche. Now, once relegated to the status of children, the budding adult had a place of his or her own, a place of music, bad or good, you pick, and protest against the "man." How silly, then, that punk itself vied to create its own subculture as a consumer aggregate, with no real interest in affecting change at all. In its non-conformist nature, punk literally created a subculture that would eventually have its own marketplace, its own capitalist structures a la Hot Topic and other such gothic-ally obsessed teen hideouts. And teenagers bought into it, hook, line, and sinker, not necessarily through some malicious attempt on the part of punk itself, but because punk provided a place for them to go, where their voices could be heard by someone, even if that someone could do nothing to alleviate the perceived issues of society itself.

Punk was at the cusp of subcultural America/Britain/Australia. In some ways, it was one of the first to take off, to become like a living thing embodied in the mind. It rejected the establishment (monarchy, democracy as fascism, etc.) and sought to ironically being non-conformist by conforming to non-conformism itself (and that might take a moment to contemplate, because punk's survival relied quite literally on non-conformism to be a form of conformist thought, without reservation). You might view all this as a push against the nation state, a sort of anti-intellectual, anti-authoritarian monster with a chip on its shoulder. It is, because punk's response to the world of the 70s and 80s relied almost exclusively on a resistance to the hierarchical structures of the nation, a rejection of what the nation state was doing or had done, and where it would go in the future.

Punk style is forgettable, but its history, its move from a seemingly obscure subculture to universally recognized and commidified almost-dominant-culture, is not. It sat at the dawn of the invention of the goth, the black honky-tonk, the Christian rock movement, the punk music we are familiar with today, and various other movements that otherwise might not have existed if punk itself had not seized capitalism by its throat and wrangled the life out of it until the two could finally agree that they could work together. Too bad that punk got the raw end of the deal, because, after all, for something so dead set against capitalism and the nation state, punk has easily assimilated, if not without the occasional angered retort, into the dominant structures of nationhood and commidification.

That is what punk is. It is not Green Day, for the punk music scene is nothing more than a dilution of what used to be legitimate attempts as subversion complicated by contradiction.

Perhaps that question rises again: where am I going with this? To understand cyberpunk, biopunk, greenpunk, steampunk, salvagepunk, and all the other punks that fans and literature enthusiasts have come up with, one must know where the suffix "punk" comes from. One must know the the mouth of the beat before knowing the beast itself.

Any questions or disagreements?

--------------------------------

Read Part One (Punking), Part Three (Cyberpunk A), Part Four (Cyberpunk B), and Part Five (Cyberpunk C).

Where am I getting at with this? The very nature of "punk," as I conceive it, is that it cannot ever truly reject the dominant culture, capitalism, not if it, as a movement, expects to survive. Here you might ask: what is "punk?" You would be right to ask that.

Punk originated, somewhat, in music in the 1970s or so, as many have claimed. True punk, the real, commodity-rejecting monstrosity that emerged quite literally as a counter-culture rather than a subculture, was largely a response to globalization, urbanity, and post-industrialization, an inherently commodity-rich point in our history that readily acknowledged the corporation as almost human. Curious as that may sound, it seems to make sense, because as capitalism began to spread across the globe, largely not by its own steam, but through the hands of those with the guns, so to speak, it gave new powers to the corporate entity to represent itself as a thing that could "speak for itself." More curiosity abounds here as to why it took hardly any time at all for something inhuman in nature, almost robotic, to assume the vocalized subaltern without having had to shed blood in the process; well, at least not the corporate blood, but certainly the blood of pre-nationalist societies consumed into globalizing nationhood.

Punk originated, somewhat, in music in the 1970s or so, as many have claimed. True punk, the real, commodity-rejecting monstrosity that emerged quite literally as a counter-culture rather than a subculture, was largely a response to globalization, urbanity, and post-industrialization, an inherently commodity-rich point in our history that readily acknowledged the corporation as almost human. Curious as that may sound, it seems to make sense, because as capitalism began to spread across the globe, largely not by its own steam, but through the hands of those with the guns, so to speak, it gave new powers to the corporate entity to represent itself as a thing that could "speak for itself." More curiosity abounds here as to why it took hardly any time at all for something inhuman in nature, almost robotic, to assume the vocalized subaltern without having had to shed blood in the process; well, at least not the corporate blood, but certainly the blood of pre-nationalist societies consumed into globalizing nationhood. Punk, to try to simplify here for brevity, invented for us the teenager as a market niche. Now, once relegated to the status of children, the budding adult had a place of his or her own, a place of music, bad or good, you pick, and protest against the "man." How silly, then, that punk itself vied to create its own subculture as a consumer aggregate, with no real interest in affecting change at all. In its non-conformist nature, punk literally created a subculture that would eventually have its own marketplace, its own capitalist structures a la Hot Topic and other such gothic-ally obsessed teen hideouts. And teenagers bought into it, hook, line, and sinker, not necessarily through some malicious attempt on the part of punk itself, but because punk provided a place for them to go, where their voices could be heard by someone, even if that someone could do nothing to alleviate the perceived issues of society itself.

Punk, to try to simplify here for brevity, invented for us the teenager as a market niche. Now, once relegated to the status of children, the budding adult had a place of his or her own, a place of music, bad or good, you pick, and protest against the "man." How silly, then, that punk itself vied to create its own subculture as a consumer aggregate, with no real interest in affecting change at all. In its non-conformist nature, punk literally created a subculture that would eventually have its own marketplace, its own capitalist structures a la Hot Topic and other such gothic-ally obsessed teen hideouts. And teenagers bought into it, hook, line, and sinker, not necessarily through some malicious attempt on the part of punk itself, but because punk provided a place for them to go, where their voices could be heard by someone, even if that someone could do nothing to alleviate the perceived issues of society itself.Punk was at the cusp of subcultural America/Britain/Australia. In some ways, it was one of the first to take off, to become like a living thing embodied in the mind. It rejected the establishment (monarchy, democracy as fascism, etc.) and sought to ironically being non-conformist by conforming to non-conformism itself (and that might take a moment to contemplate, because punk's survival relied quite literally on non-conformism to be a form of conformist thought, without reservation). You might view all this as a push against the nation state, a sort of anti-intellectual, anti-authoritarian monster with a chip on its shoulder. It is, because punk's response to the world of the 70s and 80s relied almost exclusively on a resistance to the hierarchical structures of the nation, a rejection of what the nation state was doing or had done, and where it would go in the future.

Punk style is forgettable, but its history, its move from a seemingly obscure subculture to universally recognized and commidified almost-dominant-culture, is not. It sat at the dawn of the invention of the goth, the black honky-tonk, the Christian rock movement, the punk music we are familiar with today, and various other movements that otherwise might not have existed if punk itself had not seized capitalism by its throat and wrangled the life out of it until the two could finally agree that they could work together. Too bad that punk got the raw end of the deal, because, after all, for something so dead set against capitalism and the nation state, punk has easily assimilated, if not without the occasional angered retort, into the dominant structures of nationhood and commidification.

That is what punk is. It is not Green Day, for the punk music scene is nothing more than a dilution of what used to be legitimate attempts as subversion complicated by contradiction.

Perhaps that question rises again: where am I going with this? To understand cyberpunk, biopunk, greenpunk, steampunk, salvagepunk, and all the other punks that fans and literature enthusiasts have come up with, one must know where the suffix "punk" comes from. One must know the the mouth of the beat before knowing the beast itself.

Any questions or disagreements?

--------------------------------

Read Part One (Punking), Part Three (Cyberpunk A), Part Four (Cyberpunk B), and Part Five (Cyberpunk C).

Posted by

Unknown

at

7:28 PM

4

comments

Labels:

Fantasy Factoids,

Literature Rants,

Science Factoids

Labels:

Fantasy Factoids,

Literature Rants,

Science Factoids

Monday, August 31, 2009

Punking Everything in SF/F (Part One): The Present